A major challenge for De Beers and the diamond industry is that diamonds are, by their nature, not perishable. In order for the industry to grow, the demand for diamonds has to grow or steady production would eventually lead to oversupply. If the supply exceeds demand, the price would drop and the industry would not be able to sustain a price for diamonds that maintained their status as a luxury good.

Given that the jewelry market accounts for more than two-thirds of rough diamond sales, De Beers bypassed its distribution channels and tailored its marketing campaign to the end consumer. They figured that if they created enough consumer demand, the benefits would pass through the retailer, wholesalers and cutters to benefit De Beers which controlled the mining and distribution of rough diamonds. The result is a brilliant marketing strategy.

Given that the jewelry market accounts for more than two-thirds of rough diamond sales, De Beers bypassed its distribution channels and tailored its marketing campaign to the end consumer. They figured that if they created enough consumer demand, the benefits would pass through the retailer, wholesalers and cutters to benefit De Beers which controlled the mining and distribution of rough diamonds. The result is a brilliant marketing strategy.

Much of the success of De Beers has been created by this global campaign, one of the first-and most intensively pursued-ever implemented. Key objectives of the campaign have been to create an image of diamonds that:

- Positions diamonds at the peak of the Maslow hierarchy of needs-a luxury whose cost is nothing compared to its value

- Diamonds are a gift of love-the larger and finer the diamond, the greater the love; and as a symbol of love, they should never be resold

- Diamond rings are the only choice to mark an engagement; a regular stream of engagements is assured in modern society.

A Diamond Is Forever

De Beers needed a slogan for diamonds that expressed both the theme of romance and of legitimacy. Then in 1948 a copywriter for De Beers’ advertising company, N. W. Ayer, came up with the caption “A Diamond Is Forever,” which was scrawled on the bottom of a picture of two young lovers on a honeymoon. Even though diamonds can be in fact shattered, chipped, discolored or incinerated to an ash, the concept of eternity perfectly captured the magical qualities that the advertising agency wanted to impute to diamonds. Within a year, “A Diamond Is Forever” became the official logo of De Beers.

De Beers needed a slogan for diamonds that expressed both the theme of romance and of legitimacy. Then in 1948 a copywriter for De Beers’ advertising company, N. W. Ayer, came up with the caption “A Diamond Is Forever,” which was scrawled on the bottom of a picture of two young lovers on a honeymoon. Even though diamonds can be in fact shattered, chipped, discolored or incinerated to an ash, the concept of eternity perfectly captured the magical qualities that the advertising agency wanted to impute to diamonds. Within a year, “A Diamond Is Forever” became the official logo of De Beers.

In 1951, N. W. Ayer found some resistance to its million dollar publicity blitz. It noted in its annual strategy review: “The millions of brides and brides-to-be are subjected to at least two important pressures that work against the diamond engagement ring. Among the more prosperous, there is the sophisticated urge to be different as a means of being smart…. The lower-income groups would like to show more for the money than they can find in the diamonds they can afford.”

To remedy these problems, the advertising agency argued that “it is essential that these pressures be met by the constant publicity to show that only the diamond is everywhere accepted and recognized as the symbol of betrothal.”

N. W. Ayer was constantly searching for new ways to influence American public opinion during this period. The ad firm exploited the relatively new medium of television by arranging for actresses and other celebrities to wear diamonds when they appeared before the camera. It also established a “Diamond Information Bureau,” which placed a quasi-official stamp of authority on the flood of “historical” data and “news” it released.

N. W. Ayer was constantly searching for new ways to influence American public opinion during this period. The ad firm exploited the relatively new medium of television by arranging for actresses and other celebrities to wear diamonds when they appeared before the camera. It also established a “Diamond Information Bureau,” which placed a quasi-official stamp of authority on the flood of “historical” data and “news” it released.

To exploit this psychological need of Americans to conspicuously display symbols of their wealth, N. W. Ayer specifically recommended: “Promote the diamond as one material object which can reflect, in a very personal way, a man’s … success in life.” Since this campaign would require advertisements addressed to upwardly mobile men, the ad agency suggested that ideally they “should have the aroma of tweed, old leather and polished wood which is characteristic of a good club.” In other words they were to evoke in men the sweet smell of success.

For some sixteen years, N. W. Ayer carefully cultivated the romantic image in the public’s mind that a diamond was a unique manifestation of nature and the rarest of all precious objects in the world. Then, in 1955, the General Electric Company announced with considerable fanfare that it had invented a process for manufacturing diamonds from ordinary carbon, which was the most common element on earth. At the request of De Beers, the advertising agency immediately began feeding stories to the press intended to dispel fears that the mass production of cheap diamonds was imminent. The crisis of synthetic diamonds soon passed from public attention.

De Beers reinforced the notion of eternal love by instilling the concept that diamonds have an eternal sentimental value. This made it much less likely that diamond owners would resell their diamonds. The end result of this campaign is that women, who make up more than 90 percent of diamond owners, are trained to measure their partner’s devotion in terms of carats and brilliance. Most expect to keep their diamonds forever and to pass them to other family members because of their sentimental value.

In the mid-1950s, Russian diamonds entered the market. However, a large volume of these diamonds were smaller than the typical engagement diamond so this created a new challenge for the De Beers marketing strategy. De Beers again resorted to advertising, this time introducing the public to the eternity ring, which couples were encouraged to purchase when they renewed their wedding vows. The eternity ring with a row of smaller diamonds around the finger quickly absorbed the new supply of smaller stones.

In the mid-1950s, Russian diamonds entered the market. However, a large volume of these diamonds were smaller than the typical engagement diamond so this created a new challenge for the De Beers marketing strategy. De Beers again resorted to advertising, this time introducing the public to the eternity ring, which couples were encouraged to purchase when they renewed their wedding vows. The eternity ring with a row of smaller diamonds around the finger quickly absorbed the new supply of smaller stones.

International

The campaign to internationalize the diamond invention began in earnest in the mid-1960s. The prime targets were Japan, Germany, and Brazil. Within ten years, De Beers succeeded beyond even its most optimistic expectations, creating a billion-dollar-a-year diamond market in Japan, where matrimonial custom had survived feudal revolutions, world wars, industrialization, and even the American occupation.

Until the mid-1960s, Japanese parents arranged marriages for their children through trusted intermediaries. The ceremony was consummated, according to Shinto law, by the bride and groom drinking rice wine from the same wooden bowl. There was no tradition of romance, courtship, seduction, or prenuptial love in Japan; and none that required the gift of a diamond engagement ring. Even the fact that millions of American soldiers had been assigned to military duty in Japan for a decade had not created any substantial Japanese interest in giving diamonds as a token of love.

Until the mid-1960s, Japanese parents arranged marriages for their children through trusted intermediaries. The ceremony was consummated, according to Shinto law, by the bride and groom drinking rice wine from the same wooden bowl. There was no tradition of romance, courtship, seduction, or prenuptial love in Japan; and none that required the gift of a diamond engagement ring. Even the fact that millions of American soldiers had been assigned to military duty in Japan for a decade had not created any substantial Japanese interest in giving diamonds as a token of love.

De Beers began its campaign by suggesting that diamonds were a visible sign of modern Western values. It created a series of color advertisements in Japanese magazines showing beautiful women displaying their diamond rings. All the women had Western facial features and wore European clothes. Moreover, the women in most of the advertisements were involved in some activity — such as bicycling, camping, yachting, ocean swimming, or mountain climbing — that defied Japanese traditions. In the background, there usually stood a Japanese man, also attired in fashionable European clothes. In addition, almost all of the automobiles, sporting equipment, and other artifacts in the picture were conspicuous foreign imports. The message was clear: diamonds represent a sharp break with the Oriental past and a sign of entry into modern life.

The campaign was remarkably successful. Until 1959, the importation of diamonds had not even been permitted by the postwar Japanese government. When the campaign began, in 1967, not quite 5 percent of engaged Japanese women received a diamond engagement ring. By 1972, the proportion had risen to 27 percent. By 1978, half of all Japanese women who were married wore a diamond; by 1981, some 60 percent of Japanese brides wore diamonds. In a mere fourteen years, the 1,500-year Japanese tradition had been radically revised. Diamonds became a staple of the Japanese marriage. Japan became the second largest market, after the United States, for the sale of diamond engagement rings.

Recent Campaigns

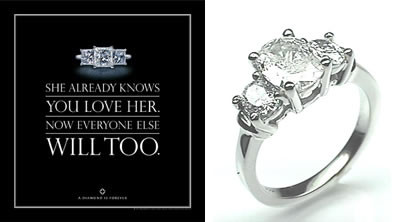

With the continued success of its existing marketing campaigns, De Beers sought new avenues to increase diamond demand. In January 2000, they announced an extensive marketing campaign for the “three-stone diamond anniversary ring”, which featured a center stone flanked by two smaller-sized side-stones. The three-stone ring initiative was targeted at couples celebrating their anniversary. Research conducted by the advertising agency showed that female consumers shared a “desire to take stock of their relationship in the present day, reflect upon the journey shared as a couple, and look forward to the many happy years that lay ahead”. The three-stone ring was tailor made for each facet of the relationship: Past, present and future. The three-stone ring campaign was a tremendous success.

De Beers created a Bigger is Better campaign that was aimed at stimulating women’s desire for larger diamonds. The ad agency’s research found that 82% of survey respondents desired jewelry with a diamond of at least a half-carat, but few actually received such stones. The “Diamonds that Make a Statement” campaign was targeted at 25-54 year old affluent married couples, earning a combined household income of at least $75,000. It featured products such as stud earrings and solitaire necklaces.

The ads debuted in September 2002 featuring diamonds and advertising copy on an all-black background. Each advertisement consisted of two panels. One panel showed a smaller diamond, the other showed the same design with a larger diamond. Accompanying the photographs were humorous catchphrases like “Thank you, Bob … Thank you, Lord.”

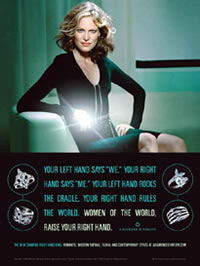

Constantly seeking new avenues to stimulate diamond demand, De Beers in September 2003, launched the “Women of the World Raise Your Right Hand” print campaign targeted at the evolved, affluent, fashion savvy woman who has probably been married at some point, previously received diamond jewelry, and needs no one’s permission to indulge herself. The target group for this campaign, women aged 35 to 64, is slightly older than in other campaigns. Each advertisement features four ring styles – modern vintage, contemporary, floral and romantic – and a photo of a stylish woman who exemplifies the target audience. The ad copy encourages women to think of rings for their right hands as expressions of personal style for the independent, worldly, assertive sides of their personalities.

Constantly seeking new avenues to stimulate diamond demand, De Beers in September 2003, launched the “Women of the World Raise Your Right Hand” print campaign targeted at the evolved, affluent, fashion savvy woman who has probably been married at some point, previously received diamond jewelry, and needs no one’s permission to indulge herself. The target group for this campaign, women aged 35 to 64, is slightly older than in other campaigns. Each advertisement features four ring styles – modern vintage, contemporary, floral and romantic – and a photo of a stylish woman who exemplifies the target audience. The ad copy encourages women to think of rings for their right hands as expressions of personal style for the independent, worldly, assertive sides of their personalities.

The Next Big Push

The 1990’s saw diamonds losing out to other luxury goods in terms of share of luxury spending. That trend is changing with renewed efforts by De Beers. This is due partly to an industry advertising push initiated by De Beers that aims to treble total marketing expenditure to more than $1.5 billion.

De Beers has pressured its site holders (those who buy its diamonds) to increase their contribution to the marketing budget following the introduction of its so-called “supplier of choice”, which cut the number of dealers to which the company sells. And it is recruiting high end retailers to increase further marketing expenditures.

The company’s move to improve its product’s branding has been helped by a venture with the French company LVMH to open diamond stores worldwide, including a flagship site on London’s Bond Street. De Beers is setting out to change what jewelry stores look like. They acknowledge that traditionally, the bravest thing you could do was to go in the door of a jewelry store. They now vow to change that and are willing to invest in marketing jewelry in a modern way.